His 1773 tour of Scotland’s rugged west gave birth to one of travel literature’s sharpest, driest, and most enduring critiques of paradise

When the Englishman Samuel Johnson set sail for the Western Isles of Scotland in 1773, he wasn’t chasing golden sunsets or balmy beaches. He wasn’t trying to write the next breezy bestseller about charming locals and quaint cobblestone villages. In fact, Johnson, the famously curmudgeonly lexicographer, essayist, and intellectual, didn’t seem particularly thrilled to be going at all.

But go he did — and from that reluctant journey emerged A Journey to the Western Islands of Scotland, a travel account that’s still read and studied nearly 250 years later. As Americans and Scots alike rediscover Johnson’s writing in 2025, amid new editions and travel retrospectives, the book reminds us that travel doesn’t always have to be Instagrammable to be meaningful.

When Luxury Was a Dry Blanket and a Roof

The Hebrides of the 18th century were not designed for tourists. Roads were few, inns were basic, and rainfall was generous. Johnson, already in his 60s and unused to roughing it, recorded everything with equal parts irritation and fascination.

Beds were lumpy. Food was plain. Conversation was, at times, awkward. And yet, it’s exactly these discomforts that give his account texture. “A man who has not been in the Hebrides,” Johnson famously quipped, “has not been in Scotland.” Whether that was a compliment or a complaint is still up for debate.

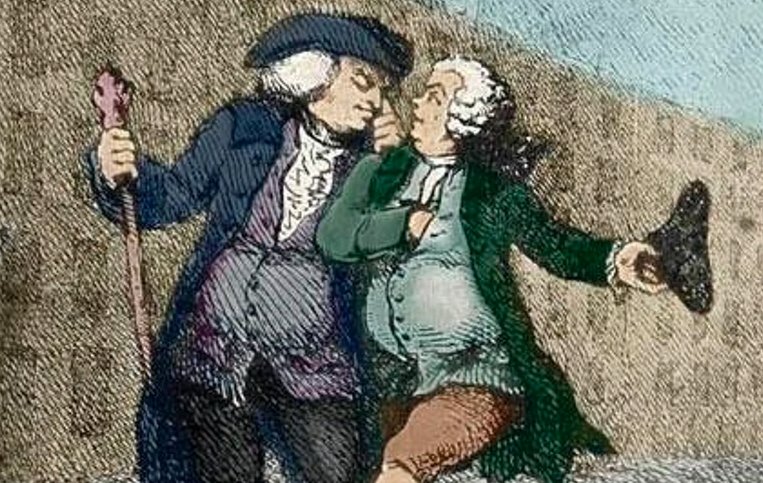

Johnson travelled with his young Scottish friend James Boswell, who would later pen the legendary Life of Johnson. Their companionship — Johnson’s weary wit paired with Boswell’s wide-eyed enthusiasm — makes for a sort of literary buddy comedy with bagpipes.

Literature Born of Misfortune

Modern travel writing often falls into a predictable rhythm of exotic praise — sunsets over vineyards, café conversations with smiling strangers, barefoot beach walks. But as literary critic V.S. Pritchett dryly observed, that’s often where it fails:

“A large number of travel books fail simply because of the intolerable, monotonous good luck of their authors.”

Johnson’s journey succeeds precisely because everything goes slightly wrong — and he writes about it with brutal honesty. There’s no airbrushing. When lodgings are bad, he says so. When the conversation turns strange or the path gets muddy, it goes into the book.

He finds beauty too — the vast skies, the fierce independence of islanders, the rhythm of Gaelic culture — but it’s never idealized. His praise, when it comes, feels earned.

Out of His Element, Into Himself

For all his crusty complaints, Johnson’s time in Scotland softened him in surprising ways. The journey offered him not just a change of scenery but a confrontation with his own biases. He admired the resilience of Highland communities, even as he struggled to understand them. He worried about the erosion of ancient traditions, especially the Gaelic language, which was already being pushed aside by modernization.

In one moment of candid reflection, he admits to feeling something akin to wonder at the spiritual simplicity and generosity of the people he meets — a far cry from his grumbles about cold rooms or questionable cooking.

This emotional arc, from disdain to depth, is what gives Johnson’s travelogue its lasting power. It isn’t just about Scotland; it’s about what happens when a person leaves behind the familiar and finds themselves disoriented, frustrated — and changed.

The Hebrides Today: Still Wild, Still Worth It

In 2025, the Hebrides are more accessible than in Johnson’s time — ferries run on schedule, and the inns now have WiFi. But the spirit of the place hasn’t changed. The winds still blow hard, the roads still narrow, and the silence in the hills can still unsettle or inspire, depending on the traveller.

For those revisiting Johnson’s Journey today, it offers a refreshing antidote to glossy brochures and travel influencer reels. It’s a reminder that true travel isn’t always comfortable. It’s often muddy, awkward, humbling — and all the more memorable for it.